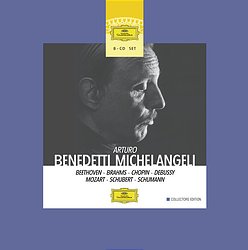

ARTURO BENEDETTI MICHELANGELI

BEETHOVEN: Klavierkonzerte / Piano Concertos

Nos. 1, 3, 5 · Klaviersonate / Piano Sonata

No. 4 · BRAHMS: 4 Balladen op. 10 · SCHUBERT:

Klaviersonate / Piano Sonata D 537 · CHOPIN:

10 Mazurkas · Prélude op. 45 · Ballade op. 23

Scherzo op. 31 · DEBUSSY: Préludes · Images

Children's Corner · MOZART: Klavierkonzerte

Piano Concertos Nos. 13, 15, 20, 25 · SCHUMANN:

Carnaval · Faschingsschwank aus Wien

Wiener Symphoniker · NDR-Sinfonieorchester

Carlo Maria Giulini · Cord Garben

CD DDD 469 820-2 GB 8

AAD / ADD (partly)

8 Compact Discs

Collectors Edition

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli

"I do not play for others," Michelangeli once confessed, "but only for myself in the service of the composer. It makes no difference whether there is an audience or not; when I am at the keyboard I am lost. And I think of what I play, and of the sound that comes forth, which is a product of the mind." When he walked out onto the platform, according to the testimony of one close associate, he was often enveloped in a mysteriously self-induced trance, which excluded consciousness of everything but the music. Like many people perceived as arrogant and cold, he was in fact intensely shy, and his notoriously unsmiling demeanour on the platform derived from his belief that applause should be for the composer, not the performer.

It must be admitted that both pianistically and interpretatively Michelangeli, to use a current phrase, was the ultimate "control freak", sparing no pains in his quest for unbreachable security. "If one never worried about doing something that requires such infinite care and skill, one would be an idiot," he once remarked. "The relaxed ones are the idiots. There is always the unpredictable element, the possibility that something may go wrong." The idea, however, that as a performer he was tantamount to an automaton, or as reliably consistent as a fine-tuned computer, is mistaken. His command of the keyboard was indeed awe-inspiring, though not perhaps quite as unique as contemporary legend would have it (Hofmann, Godowsky, Horowitz and Richter were hardly his inferiors, nor indeed are his pupils Argerich and Pollini), his accuracy just this side of superhuman (though there's at least one reassuring fluff in the present collection), his pedalling as deft and subtle as his fingering, his tonal palette apparently infinite, and deployed and controlled with astonishing precision - never more so than in the present performances of the Debussy Préludes (sample "La Puerta del Vino" on CD 8 for starters).

In his long, though sometimes interrupted, career, Michelangeli reputedly cancelled more concerts than he gave (generally a combination of perfectionism and arthritis), and his repertoire is still widely reputed to be among the smallest in pianistic history. The facts, as demonstrated even in the present collection, tell a different story. Indeed the works he performed and recorded were greater in number and wider in range than those of many stellar icons, and he carried in his head and fingers most, if not all of the 32 Beethoven Sonatas, most of the works of Chopin, many of the piano works of Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Liszt, and, perhaps surprisingly, a lot of Reger (like his great compatriot Busoni, he was in many ways more Germanic than Latin). He championed Schoenberg, though he openly despised much music of the later 20th century, and gave many loving performances of Bach (whom he later decided not to play on the piano, confining his Bach playing to the organ, though never in public). In addition to his core repertoire of Scarlatti, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Brahms, Debussy and Ravel, he played a wealth of Albéniz, Balakirev, Falla, Galuppi, Granados, Grieg, Martucci, Mompou, Paradisi, Respighi, Tchaikovsky, Tomeoni and Weber, and he adored Rachmaninov (while recording, curiously, only the seldom heard Fourth Concerto).

He was also an accomplished violinist, playing the instrument since the age of three - a fact that has strangely eluded the standard Michelangeli mythology and remains little known even today. At ten he entered the Milan Conservatory, where he finally opted for the piano, graduating with honours three years later. In 1939 he entered the International Piano Competition at Geneva and won, to nobody's surprise (the great Alfred Cortot proclaimed him "a new Liszt"). Barely out of his teens, he now astonished everyone by evidently spurning the glittering career that awaited him and becoming a professor of piano at the Conservatory in Bologna, while simultaneously entering medical school, where he remained for five years. He abandoned medicine but remained a teacher for much of his life, numbering among his many pupils (whom he accommodated and taught free of charge) not only Argerich and Pollini but Ivan Moravec, Jörg Demus, Walter Klien and Adam Harasiewicz. During the Second World War he served as a pilot in the Italian Air Force before joining the anti-Fascist underground. There followed eight months of incarceration by the Nazis, reputedly brought to an end by a spectacular escape. He was also an enthusiastic racing-car driver who entered (but did not win) the Mille Miglia auto race. With all this, one might well ask, who needs legends?

Like many, perhaps even most, of the greatest artists, Michelangeli was always controversial, often arousing outspoken hostility in his fellow musicians (one described him as "the Great Mortician"), while in others inspiring a degree of idolatry hardly seen since the heyday of Liszt in the 19th century. To numerous others, however, he remained an enigma - even to some of his friends, one of whom wrote in his diary, "Beyond reproach, as ever. The notes exactly as written. Technically perfect. Yet it all remains glacial." And later: "He is a real perfectionist. But I think this fanaticism and the extreme instrumental standards he sets for himself prevent his imagination from taking flight, and stop him expressing any real love for the work he's performing so impeccably. It is 'inspiration' that's missing. But - one doesn't judge a master. ... I've no wish to criticize a great artist." These are not the words of a mere critic - they come from one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Sviatoslav Richter (and in writing thus, he spoke for many). Even at this exalted level, musical reactions are notoriously subjective. But in one respect (like many other commentators, it must be said), Richter was not being strictly accurate. Very often, and as designedly as he did everything else, Michelangeli did not play the notes "exactly as written".

A frequent though not consistent feature of his playing, evidenced repeatedly in the present collection, in a wide range of music, was the calculated non-synchronization of the hands - almost a cliché among 19th-century Romantics, as typified by Paderewski, but a rarity indeed among their conscientiously "objective" 20th-century counterparts and emphatically not indicated in the score. For Michelangeli, needless to say, the device was no casual, self-indulgent or automatic mannerism but a means of illuminating the harmonic basis of even the most polyphonic textures. It was also, as one of his pupils, Renato Premezzi, has pointed out, a means of "allowing the bass to set up and enhance the treble", thus enriching the dimensions of sonority. And no pianist ever gave more concentrated attention to sonority than Michelangeli. The roots of his obsession, however, were not what one might imagine. To begin with, he actively disliked the piano, finding it altogether too percussive. Early on in his musical life, he stopped listening to other pianists, withdrew into himself and began studying on his own. "I discovered that the sounds made by the organ and the violin could be translated into pianistic terms", he told an interviewer. "If you speak of my tone, you must not think of the piano, but a combination of the violin and the organ."

If Michelangeli's phenomenal pianism was consistent throughout his career (he had mastered Brahms's fiendish Variations on a Theme of Paganini by the time he was 14), his interpretations over the years were not. Contrary to his reputation in certain circles, he was not an artist whose vision of a work ossified into a single, eternal conception. His several recorded performances of Ravel's Gaspard de la nuit, like his Beethoven recordings, show significant differences. Nor, greatly to his credit, was he consistent in his approach even to a single composer. As CDs 1 & 2 make abundantly plain, it is nonsense to talk about "Michelangeli's Mozart". Each work is approached from a standpoint almost entirely dictated by the intrinsic character and properties of the piece itself, as seen by Michelangeli at that particular time. Nothing reveals this more strikingly than his use of the piano itself. It seems unlikely that any pianist in history has had a more sovereign control or commanded a wider range of tone colours. The chances of his achieving any quality of sound by mistake are virtually non-existent.

Despite his near obsession with sonority, he was too scrupulous a musician to cultivate it for its own sake. He used it not only for expressive and atmospheric but also for structural purposes. So it is of more than ordinary interest that his chosen sound world for each of the four Mozart Concertos recorded here is unique to that particular performance. Compare the piano entries in the two C major Concertos, for instance. They might have come from two different pianists, as well as two different instruments. His reasoning and convictions were not always easy to understand, but given the artistic integrity, the tireless intellect and the intense dedication of the man at the keyboard, it behoves us to try. He may persuade us, or he may not, but he demands our attention.

Jeremy Siepmann

In: http://www.deutschegrammophon.com/

3 comments:

You have really great taste on catch article titles, even when you are not interested in this topic you push to read it

You could easily be making money online in the undercover world of [URL=http://www.www.blackhatmoneymaker.com]blackhat money making[/URL], It's not a big surprise if you don't know what blackhat is. Blackhat marketing uses not-so-popular or misunderstood ways to produce an income online.

[url=http://www.23planet.com]Online casinos[/url], also known as arranged casinos or Internet casinos, are online versions of acknowledged ("cobber and mortar") casinos. Online casinos set excepting gamblers to filch up and wager on casino games fully the Internet.

Online casinos superficially set up up as a replacement during these days odds and payback percentages that are comparable to land-based casinos. Some online casinos exhort on higher payback percentages with a rate gouge match automobile games, and some gamble extinguished payout match audits on their websites. Assuming that the online casino is using an correctly programmed unspecific consolidate up generator, note games like blackjack coveted an established borderline edge. The payout shard fully despite these games are established be means of the rules of the game.

Dissimilar online casinos agree into part publicly mind or beget their software from companies like Microgaming, Realtime Gaming, Playtech, Worldwide Cunning Technology and CryptoLogic Inc.

Post a Comment